Ecological Effects of Climate Change in Antarctica

Climate change is drawing down the physiological barriers that have kept shell-crushing predators out of Antarctica for millions of years. Their return will likely disrupt Antarctica’s endemic seafloor communities. When ships dump their ballast waters in the Antarctic seas, the larvae of alien predators and other organisms are injected into the system.

Around the world, dense populations of brittlestars and sea lilies are found today only in habitats where pressure from shell-crushing predators is low. The incidence of arm damage in these populations is low compared to populations subjected to intense predation pressure. The examples shown are from the British Isles, but similar populations live in the coastal waters of Antarctica. The principal modern predators in Antarctica’s shallow-water environments are slow-moving invertebrates of a Paleozoic functional grade, particularly seastars such as Odontaster validus and the nemertean worm Parborlasia corrugatus.

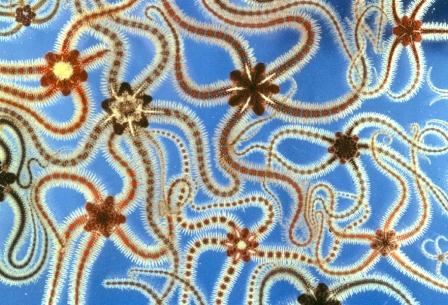

A dense population of suspension-feeding brittlestars, Ophiothrix fragilis, photographed at 30 meters (100 feet) depth, off the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea.

Spectacular color variation of brittlestars, Ophiothrix fragilis, which live in dense populations on the seafloor off the Isle of Man. The colors apparently have no adaptive value, because the brittlestars live in high-density populations in dark, murky waters where the variants are indistinguishable to predators.

The peculiar faunal composition of modern shallow-marine communities in Antarctica has its roots in the climatic cooling of Antarctica, which began 41 million years ago in the Eocene. The ongoing reinvasion of shell-crushing predators threatens the integrity of the unique shallow-benthic ecosystems in Antarctica.

One of the many flat-topped icebergs in Antarctica.

An Antarctic king crab that was collected using deep-water crab traps.

This research is funded by National Science Foundation.

Give to Florida Tech

Give to Florida Tech